Some thoughts on disjunctive difference within "the same" God

A further reply to Antonio Vargas

I am fundamentally cultus-oriented, and so just as I saw the issue of a God’s identity across distinct planes of activity—such as the intellective and the hypercosmic ‘Zeuses’, who have contradictory mythos—through the lens of the cultic reality of worshipers’ ability to recognize their God in a cultic context that contradicts their own in certain respects, so too, I think that I have more sympathy for Antonio’s position on this issue through reflecting upon the converse cultic reality, namely the freedom of worshipers not to acknowledge a contradictory cultus of their God as directed to the same God as theirs, or at least not in a univocal sense.

These two cultic realities are, after all, complementary aspects of the basic polytheist attitude. Even in the former case, worshipers are free to focalize the other manifestations of their God’s activity—for example, to see their own as ontologically prior in some fashion, and hence render the identity of the God in the two cults equivocal.

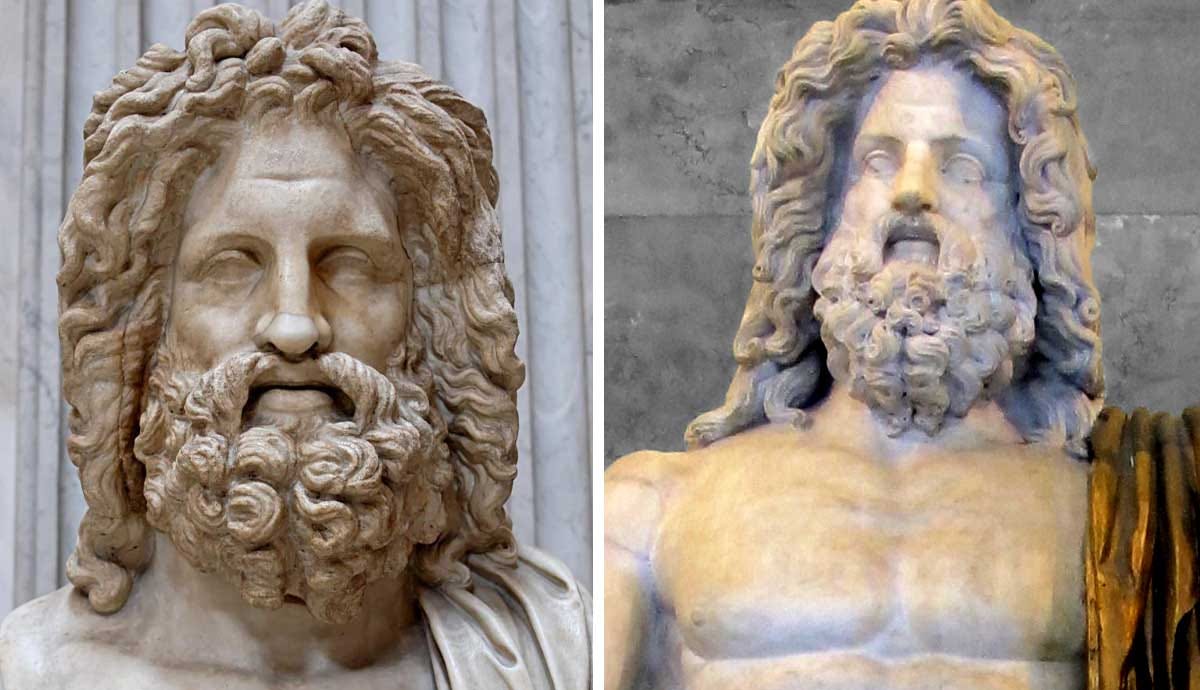

Historically, we can see that the myth Proclus reads as pertaining to ‘hypercosmic’ Zeus comes from Homer and Hesiod, particularly the former’s account of the division of the Kronian sovereignty among the three brothers, and this is the mythos we associate—broadly speaking correctly, though it is also certainly misleading to treat it as truly universal—with His ‘mainstream’ cult, whereas Proclus’ ‘intellective’ Zeus is conceived chiefly through the Orphic mythos, as well as of course Plato’s Timaeus.

The distinction between ‘intellective’ and ‘hypercosmic’ Zeus in Proclus, therefore, can also be seen through the historical lens as the distinction between the Orphic and the ‘mainstream’ cult, with the expressions of the latter being more public and popular, and of the former more private (including written works with restricted circulation) and esoteric. The former, furthermore, represents—albeit always partially and aspirationally—the ideal of a ‘pan-Hellenic’ Zeus, which is appropriately posited on an ontological plane below the more idiosyncratic.

I also think I am coming to understand better Antonio’s practice of distinguishing between the henad and the God (e.g., here). I have been resistant to making much of such a distinction, because it has typically been used by modern authors, in their ignorance of the structural imperatives of the system itself, to subordinate actual Gods to henads conceived as more sublime, and to subordinate all of Them ultimately to a reified ‘One Itself’, so that the henads are considered to be mere ‘events’ of beings participating the One.

This tendency, to which Antonio is however far too perspicuous to fall prey, comes from the two common vices of modern readers of the tradition, namely the monotheist reification of the One, on the one hand, and the privileging of the subjective experience of the participant over the principle, which is thus reduced to the event of the participant, on the other. Of the former tendency, there is no need to speak further. The latter tendency, which comes in what I would consider more and less respectable forms—the less respectable psychologistic, the more respectable phenomenological—is in any case not to be confused with Antonio’s position either. Antonio’s distinction between henad and God is rather a correctly ontological version of the ‘evental’ reading, which I think we could also associate to some degree with Reiner Schürmann’s reading of the Platonic first principle, with its deep and interesting resonance with Heidegger. Let me offer my own version of the case for it.

In a certain respect, the most idiosyncratic experience of the God is the most ontologically elevated—not insofar as it is psychological, however, but simply in its peculiarity, inasmuch as this expresses the higher principle, that of unity/individuation, and this is what gives license to the individual practitioner, or a given community of worshipers, not to acknowledge another’s experience of their God as substitutable for their own salva veritate. And this is how I think it can be legitimate to say, as I read Antonio, that the God is the henad plus the whole series of participants, and that differences between participants in respects of the formal difference of divine activities, differences such that the participating beings are formed by their experience in incommensurably different ways, therefore do not pertain to the same divine unity. In a sense, that is, the reversion gives form to what is prior to it.

The idea, as I understand it, is not that there is a henad corresponding to each unreconciled disparity of theophany, but to render dynamic and fluid the entire process in which the henad is posited. We should not think that the result is an atomized multiplicity of irreconcilable participations, however. On the contrary, in most cases, as I pointed out previously, just as individual worshipers will form communities with one another above and beyond the differences in their experience of their God, so too will these worshipers and interpretive communities seek to incorporate on their own terms, and from their own perspective, all of the other ways of experiencing and understanding their God. The henad is totalizing, but the totality is always and irreducibly perspectival.