Platonic Politics

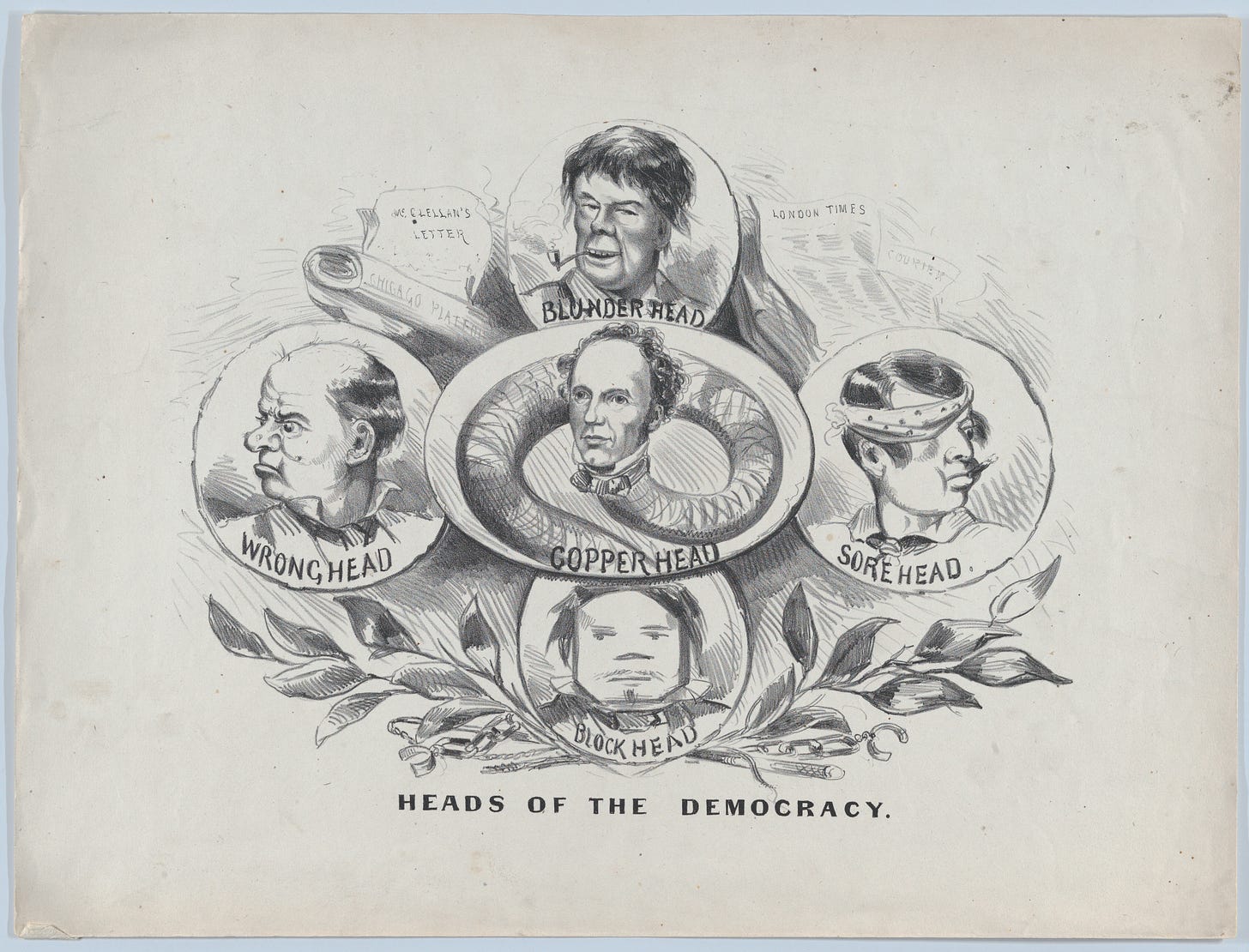

Image: A caricature of mutually destructive democratic factions in the antebellum U.S., attributed to the firm of Currier & Ives (1864)

Generally, when I speak about Plato’s Republic (in the lectures collected here—nota bene, Amazon affiliate link), I am concerned with making clear that it is not primarily a text about politics, or at least not in the simplistic sense, but rather about ‘constitution’—politeia—in a wider sense, primarily of the soul, using the constitution of a state as an analogy, grounded in the intuition that justice is a concept that can, and indeed must apply to both of these kinds of unities, to conceptualize their well-functioning integrity, the harmonious relationship among their parts. Here, though, I want to speak about the political side of this analogy, in our own, familiar sense of the ‘political’, in order to try to make certain points from those lectures more concisely. Those wishing to understand my reading in full, and to see better how my reading is grounded in the text, should consult the lectures linked above.

The city—I’ll be using the terms ‘city’ and ‘state’ indifferently to translate the term polis—the plan for which takes up the bulk of Plato’s text, could not actually exist. This is not a matter of practical constraints, but of metaphysics. It’s the form of a city, and as a form it exists right now, everywhere and nowhere—as Socrates explains, you can become a citizen of it whenever you wish, and it will inform your activity as a citizen of whatever worldly state you belong to, just as being aware of the formal or eidetic dimension of the ideas you deploy all the time in thinking and speaking informs those activities. The eidetic city is summoned at a certain point, in accord with worldly exigencies, and has a certain structured relationship to actual state forms. This comes out later in the dialogue, which circles back to shed light on the circumstances that gave rise to its inquiry, an inquiry framed by democratic crisis.

Plato begins, however, with a very different city, which is in fact Socrates’ ideal, if we are speaking about actually existing states. This is a fact one can never cease to emphasize, since popular discussions of the Republic rarely acknowledge that Socrates is fully prepared to stop right here, with his first state, which he regards as completely sufficient. Plato’s urbane brother Glaucon, however, regards it as hardly a city at all, or as a city fit only for pigs. It would be a mistake, albeit tempting, to identify this city with the way of life of contemporary and historical ‘stateless’ peoples, because while their way of life resembles in certain ways the picture Socrates paints, ‘stateless’ peoples are not frozen outside of time in a primordial way of life. Rather, as Pierre Clastres argued, those societies, far from being innocent of the state, are actively engaged in a resistance to the development of such power structures, and have carefully framed institutions accordingly. Socrates’ first city, on the contrary, has no institutions. In this ‘city’, if we can call it that, the extreme limitation of the demands placed upon resources both natural and social allows people mostly to do as they wish, and be who they are.

This state of natural and beneficent anarchy is the metaphysical baseline for the entire subsequent inquiry. It should be considered among the actually existing states, though it lies outside the sequence of state forms—aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny—because it has no organization, and is therefore strictly speaking ‘formless’. Most importantly, it has no fixed division of labor or specialized production. The trigger for the state as such in Plato’s account is the disequilibrium created by the demand for a higher standard of living than the way of life in the first city can supply, and Socrates is not shy in how he characterizes this disequilibrium: the city that Glaucon demands, he states, is ‘fevered’, sick. Hence the series of actually existing state forms will be presented, as Cinzia Arruzza remarks, “as a description of the symptomatic progression of a disease,” (A Wolf in the City, p. 114). The eidetic city Socrates proposes is thus not so much utopian as therapeutic, nor does it cure, but only manages the disease. Glaucon’s demand forces us to get clear about exactly what a state requires to the degree that it is to produce a surplus beyond sustenance—total mobilization, that is, a complete and radical reconstitution of its citizens, no longer to be present as persons, but purely as resources. To do so means to convert inherently unique, autarchic individuals, who engage with one another in the first place intersubjectively, that is, as person to person, which the text compares to people attending a sacred festival together, into replaceable organs of a larger organism, the state whose life they shall serve. The essence of the state, the paradoxical ideal to which it must aspire, is to do this humanely. The contradiction inherent in this project is why Socrates is explicit right from the start that the state as an actual, worldly phenomenon is sick, and cannot be cured, in the same way that a mortal animal, just as mortal, is already dying. The eidetic city is the medicine for what ails the state as such, but it cannot repeal the state’s mortal condition. Again, this is a logical, and not a practical matter. As with any Idea or Form, its immediate presence would be an oxymoron, for Ideas are just about mediation. An instance is not the rule, and the rule is not an instance of itself. Rather, an idea informs instances.

The idea of the state can be stated as follows: to manage the state’s sickness, the wisest people need to study each and every citizen from birth, or even before, to discern the perfect use of their innate talents for the good of the state, and assign them to that role. Once we put it in these terms, it becomes clear that this is a project not merely limited by the resources necessary to carry it out, but in fact an impossibility comparable to ‘squaring the circle’. Indeed, we may regard it in a certain respect as belonging to the same family of problems. Even granted unlimited manpower and means, it is impossible in principle to capture unique individuals according to any schema of discrete roles without remainder, that is, without misrecognition, injustice. (And of course we shall also have to reckon with the possibility that the aptitudes of individuals may change over time.)

This is precisely where the analogy between city and soul breaks down, and with a cost. At the end of the Republic, Er’s vision of the Meadow where souls choose their next life shows that many private tragedies result from this failure of the state, for as he recounts, many of those souls who make the most catastrophic choices have just come from lives in well-run states, to whose good they have contributed, but whom the state has, despite its best efforts, failed—failed, that is, to form them into beings whole in their own right. And eventually, over enough iterations, accumulated injustice will prove calamitous to the state as well—in the worst case, a tyrant mistaken for a true king.

There is an entire mathematics of eidetic misrecognition which was apparently a problem of urgent concern in the Old Academy during Plato’s lifetime and among his successors. This is why, despite how it is presented in summary accounts, the tripartite division of the soul, and the corresponding overall division of labor in the state, is explicitly provisional in Plato’s text. We are to keep seeking more parts of the soul, and more roles in the state, as far as we can go, and only then, as the Promethean method of the Philebus requires, letting the remainder run through our fingers into the infinity of the continuum. The mathematicians of the Academy had not yet carried the formula for measuring the circle into actual trillions of non-repeating digits as we have, but they were aware of a homologous metaphysical restriction preventing capture of a unique individual through a repeatable formula, a contradiction in terms. This is the point of Plato’s Parmenides, and why the Academy espoused henology, rather than ontology. It may, moreover, be why the Academy would eventually choose skepticism over the very possibility of ontology. But this would take us deeper into metaphysics, as well as into the history of ideas, than I wish at the moment to go.

For now, the political problem, plainly stated, is the impossibility of a perfect meritocracy, and this problem generates, as its necessarily flawed solutions, the series of forms of actually existing states, each of which has its programmed failure based on the fundamental misrecognition of its citizens and the true source of their virtue, so that each state form inflicts on them some distinctive and constitutive harm. The state forms Plato recognizes are aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny, each of which is based on a simple formula for sorting its citizens. There is no correct choice: all result eventually in the state’s collapse. Aristocracy sorts citizens by descent, timocracy by bravery, oligarchy by wealth, democracy by faction, and tyranny by force. Aristocracy is the first of the succession of forms simply because it is the most basic error, which comes first because it doesn’t presuppose any of the others. Aristocracy is what you get if you simply freeze the scheme of the eidetic state as if it were not provisional and impose it, giving up on evaluating each citizen as a unique, ‘autochthonous’ case and instead fixing a more or less arbitrary historical point of origin for them—for as Plato says elsewhere, trace anyone’s descent far enough back and you will find princes and slaves alike. This origin exerts a formative force upon the society until its spell wears off.

Noble descent does not guarantee virtue, of course, or even basic competence. Aristocracy thus gives way to timocracy, because martial valor, albeit a drastic oversimplification of what it means to be a ‘guardian’ of the state, is at least demonstrable here and now. The collapse into timocracy is thus a kind of realism. Since soldiers can be bought, though, a further recourse to realism brings about the collapse into oligarchy. Oligarchy is the first attempt to rationalize the state according to something both concrete and quantifiable, namely money, which can supposedly be exchanged for anything. Hence Heraclitus characterizes the very task of ontology as figuring out what stands in relation to things ‘as gold for goods’. But of course everything and everyone does not have its price. Oligarchy thus collapses into democracy, through an uprising of idealists, in effect. For the essence of democracy is that ideals and desires, taken not in their intelligibility, but rather as certain psychological orientations, can form factions, and thus exercise power, a power moreover that can transcend money, insofar as people decide for themselves what has value. None of the other state forms has simply disappeared, of course. There are aristocrats and timocrats and oligarchs around, and tyrants too, even though logically speaking tyranny ‘comes next’. The succession is ideal, not real.

The very nature of democracy for Plato, in fact, is to be a screen on which every possible way of life is projected. This is democracy’s essential ontological privilege in Plato’s text. I’m not going to argue this point, having already done so in the aforementioned lectures, and elsewhere. It should be obvious to any reader, however, that Plato is so intensely critical of democracy precisely because he lives in one, and has experienced at first hand the best and the worst it has to offer. He is candid that the democratic freedom to imagine and pursue ways of life according to diverse paradigms is indispensable to the very intellectual work he is doing. We could say, indeed, that democracy is the worldly expression of the very ‘profusion of Goods’ which Aristotle criticizes in Platonic henology. Plato could only really do the work he is doing in a democracy, the only place where this form of thought is both possible and needed, and hence he shows no similar degree of clinical interest in the other state forms, unlike those of his contemporaries who saw genuine value in aristocracy, or oligarchy, or even tyranny. The ‘Old Oligarch’ of Pseudo-Xenophon’s Constitution of the Athenians can affirm without irony that the wealthy are, by and large, the good; Plato certainly could not.

Plato’s problem, as a matter of realpolitik, is the tendency of democracy to collapse into tyranny, and the difficulty of preventing this collapse for long, a problem which is cultural and educational, and lies in the paradox that democracy can only reproduce itself if people can learn to desire difference and plurality itself, instead of choosing the tyranny of their own peculiar desire, of what seems good to them. We would need to teach them to value, beyond any particular value, what makes value possible. Instead, unfortunately, as Socrates describes it, educators in the democratic state become politicians of a sort, trying to curry favor with their students, seeking their approval. This is a natural extension of the basic formula of democracy, which is to try to assemble a faction for good, so as to eventually impose a tyranny of freedom—another oxymoron. The contradiction is inescapable. Eventually, a tyrant commands a large enough faction to be able to impose his will, for a while at least. In the best case, they might be an enlightened despot, like the best of the Roman or Chinese emperors, the most responsible, the least petty, the most hard working, who might even try to implement something of the eidetic state, such as in the Chinese examination system. At worst, the tyrant will simply embody the worst and most endemic impulses of the populace, seizing a precarious control descending almost immediately into paranoia and violence. Eventually, the tyrannical regime will be replaced by one of the other state forms. Tyranny is the terminus of the succession of state forms which culminate in democracy, so that there are two different senses of ‘end’ at work here: democracy is the ‘end’ in that it contains all the others virtually, while tyranny is the end because it represents the antithesis of the first form, aristocracy. Aristocracy reifies history and subordinates individuals completely to historically determined institutions, whereas the tyrant annuls history and subordinates institutions completely to the whims of an individual.

We must think of each regime projected upon the screen of the democratic imagination not only as a stage in the progressive development of the ‘disease’ of state formation, but as an organism in its own right, able to sustain itself for a given span of time, and reproduce itself to an extent, and therefore having a certain equivocal eidos. In this, they are not unlike the forms of animal species, which are in one respect forms, while in another respect the result of processes as in the later theory of evolutionary natural selection. In this latter sense, only the form of Animal Itself, of Animality as such, Animal Being, truly exists, because this is what every animal actually chooses, the final cause of Animal Being, which is simply to Live. So, while we see democracy in the Republic, like the other state forms, as inherently threatened, constantly haunted by the specters of the inimical forces which brought it about and will bring it down, the ‘Old Oligarch’, for his part, sees democracy instead as a hardy weed, quite capable of sustaining and reproducing itself, because sustaining it is not his concern. But for any way of life to sustain and reproduce itself entails that it has an eidetic dimension, and to that extent each of the state forms has a specific task for philosophers who would serve it. To work out in each case what this form of thought is would be a worthy project, and examples of one type or another are to be found through the history of political thought. In general terms, though, it seems that the regimes other than democracy will each affirm some substance specific to them, whereas the default philosophy in Plato’s environment, according to his view, as we know from the dialogues, is that flux ontology that he identifies as implicit in sophistical praxis. Substance-based ontologies inherently exclude something, whereas democracy is Protean, and inclusive in that sense, but incapable of sustaining itself on a purely relativistic basis.

Plato thus, as a democratic philosopher, does not opt for relativism, that is, for a reified flux, but instead for a radical, henologically-grounded pluralism. His concrete political solution is not to be found in the Republic, though, because it falls short of an eidetic solution, strictly speaking: it is that ‘mixed’ constitution which is only presented as a possibility in the Laws, a mixture of state forms tailored to specific cases, of the kind which was to prove quite durable in the Roman Republic, and would be revived under modernity. The form in which democracy’s fundamental value can be sustained, therefore, is not pure procedural democracy, but instead the mediated result of the multiplicity that democracy makes it possible to recognize, the stabilized form of this multiplicity. Culturally and cosmologically, this is what we call polytheism: the radical but stable multiplicity of value. (It needed no term in Plato’s day because it was not something anyone sought to destroy or needed, therefore, to defend.) Democracy is defined by the profusion of models, paradeigmata, just as the cosmos itself, as the Timaeus states, is the cult statue representing all the eternal Gods, that in and through which They are worshiped.

Polytheism has profound political implications, both in its radical, polycentric form, which grounds the divine field immediately in each divine individual and in one-to-one devotion—what the Hindu tradition terms bhakti—as well as in the mediated form of a hypostatized totality, the more-or-less structured ‘pantheons’ we see in each discrete polytheist tradition. The full extent of these implications was not manifest in antiquity, though in the Roman case, for example, we can see both a genetic and a functional relationship between the division of powers and the traditional priesthoods. Every center of power is at once supreme in its sphere, while also participating in a coordinate structure where their exercise inevitably overlaps, just as each of the Gods in the Olympian regime as Hesiod understands it has Their inalienable timē or prerogative, which does not exhaust Their nature; rather, all the timai together form the field of Their cooperative action.

The difference between this structure and that division of labor which is both the genesis and the undoing of the State as such is that the Gods cannot be reduced to the parts of a whole, but rather each is immediately the All, and this is how They see us as well. This, again, is a matter of metaphysics: if like is known by like, the Gods as unique individuals primarily know us as unique individuals primarily. The Gods thus hold space for the irreducibility of any individual to any project to which they lend themselves, and the inescapable responsibility of any such whole to its parts. For of any such aggregate, we would say along with Anaximander that “Whence things have their origin, there they must also pass away according to necessity; for they must pay penalty and be judged for their injustice, according to the ordinance of time.”

I don’t consider myself anything other than a general reader of TheRepublic, but I’ve never understood why it is regarded as any sort of manifesto for an actual political community rather than a theoretical study of an ideal society and the implied roles of humans inhabiting it .

So this discussion is welcome both in its emphasis on the time-bound nature of actual institutions and the extension of the argument into the implications of polytheism in the political sphere. I’m not sure that I have absorbed the totality of your argument but it provides much food for thought.